Viz editor interviewed

Chris Donald interviewed about Viz and his new book.

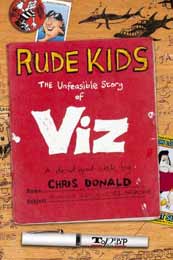

The founding editor of rude, crude and very funny humour mag Viz has just written a book. Called Rude Kids, it covers the ups and downs of Viz, including the founding of the mag, the origins of Roger Mellie the Man on the Telly, how the Viz team used to blackmail their publishers into sending them bags of used twenty pound notes, why Chris hates marketing people and much more.

We interviewed Chris about the book and Britain's sweariest comic.

Tell us a bit about the book.

Well, it's a potted history of the magazine. It starts in 1970 when I was ten, and it's got my teenage years and trainspotting in it, it's got stuff about little comic books I used to do at school, then the evolution of Viz and the whole growth from a hundred and fifty sales of the first issue up to one and a half million in the first ten years.

That's the first half of the book. Then the second half deals with problems we encountered, the frustrations of being involved in big business and my frustration with doing the magazine. The last ten years, which were downhill saleswise and psychologically, although they did have a few amusing incidents along the way. So it's an up and down tale.

Even though at the time there were depressing incidents, I can't help but write about them in a funny way. I hope the whole point of the book was to be entertaining, I didn't want it to be an earnest tome.

What were the highlights of running Viz?

It would have to be the first ten years, the exciting times when we were still working in the bedroom of my dad's house, and we were handling all the merchandise sales and subscriptions ourselves. Things were growing so fast we were actually taking huge piles of parcels off to the Post Office and everything was thrilling. We'd get phone calls from the publisher telling us that sales had leapt up in ginormous strides. The sales were going up by 50 per cent every issue, and that was all very exciting and unreal.

The first couple of times we went up to London were a bit exciting. We saw the Green Cross Code Man at Kings Cross Station – that was very exciting. But later on it becomes a bit less novel.

What was it that made Viz so successful – and why didn't that success last?

It was a word of mouth phenomenon. It had happened in Newcastle between 1980 and 1984 entirely by word of mouth. People had started hearing about the comic from their friends and going out and buying it, and sales reached saturation in Newcastle – everyone in Newcastle aged 14 to 21 had heard of the comic by 1984.

What happened from 1987-1989 was more or less the same thing, a domino effect of one person buying it or seeing a friend reading it and thinking "What's that?" and going out and getting it for themselves. Within two years the sales went from 20,000 to one and a quarter million. There was no advertising, no marketing at all, it was purely word of mouth.

And why it didn't sustain was because it had that initial impact, like the first time you see Blackadder or Fawlty Towers or something, [you think] "that's brilliant". After you've seen a whole series and then a second series and then maybe a third, it loses its initial impact. Like a bloke juggling plates – he could be just as good at juggling plates as he was five or ten years ago, but once you've seen him juggling his plates that's all there is to it really, and whether he changes the colour of his plates or the type of the design on the plates doesn't really make much difference.

So, to an extent we were a one-trick pony, and once people had seen our trick they got a bit bored and moved on to something else.

What got the best reaction?

Every now and then you did a cartoon you were aware hit the button and you immediately got a good reaction from it. Paul Whicker the Tall Vicar was the first one, in 1981, and after that Johnny Fartpants, and when the Fat Slags were launched, they had the same effect, a considerable initial impact and then they fade away.

I think the thing that sustained the most is the Top Tips feature on the letters page, because really that's a vehicle for old jokes – you can adapt any old joke into a Top Tips letter and send it in. We've been printing about twenty top tips in each comic now for about twenty years, and that's still just as popular as it always was.

Though having said that, Roger's Profanasaurus, the dictionary of euphemisms and rude words, has become quite a cult spin-off. It's gone through a few different volumes, and keeps expanding.

Were there any targets you'd never go for?

You can't really draw a line. You just go on whether something is funny or not.

Things can be both funny and offensive, but if they're funnier than they're offensive I would have gone with it. But you measure the funniness and the offensiveness in different units, and it's hard to tell.

Somebody could tell you a joke and it could be offensive, but if you laugh at it and then go "Oh dear, that was offensive," then I would say that was alright. But if you cringe first and go "Oh my god, that's a bit tasteless" then [no]. I can't think of any one subject where you can go broadly, "Ooh, that's off-limits". Somebody, somewhere out there on the internet is going to come up with a joke, no matter how grim. Even after 9/11 somebody somewhere will have written the first joke and emailed it off.

What makes a cartoon good or bad?

It just has to be funny. If it makes you laugh then that's all that you can do really. Having said that, I could think something was funny and I could read it out to the other three or four people in the office, and if none of them laughed then I'd know I was wrong and it wasn't funny. Initially you trust your own judgement, but then when you try it out on someone else you have to trust their judgement as well.

We did print bad cartoons. I would say roughly thirty per cent of the cartoons I printed I wouldn't have put in if I'd had anything better.

A bad cartoon would be one where you were aware that the person who wrote it was trying to be funny. You've got to be able to read it and not be aware of the person writing it. You've got to believe it, not go, "Oh, I can see through this." If you can see through something, it's not going to be funny. It's like a comedian on stage, once you start looking at him and going, "I don't like the look of him," then you're not going to find anything he says funny.

What sort of thing did you work on at Viz?

Originally when we first started, I was the main contributor, and as I took on more people to draw cartoons, gradually my input into the cartoon side of things reduced, until eventually I was doing only one cartoon an issue.

But I was always doing all the written stuff, all the tabloid spoofs, stuff like that, and editing the letters pages. But I think the hardest thing I did was keeping everybody happy. On one side I had the publishers to keep happy, and on the other side I had my editorial staff to keep happy, and the two sides were completely different. There was forever friction between the two offices, the editorial in Newcastle and the publishing in London. It was a bit like juggling plates, trying to keep everybody happy at once.

What proportion of the readers' letters did you make up?

Generally speaking, on an average letters page, ten per cent of them would be sent in by readers and didn't need any editing and you'd put them straight in. Probably about sixty per cent would be sent in by readers but they'd need some considerable amount of editing, and then the other thirty per cent we'd make up ourselves.

Did you ever get odd items sent in to you?

Yeah, people used to send all sorts of things into the letters page, because we would print packaging from strangely named foreign things, and people would send us packets of biscuits and things.

Once, I don't know why, we actually asked people to send in pornographic magazines. It was a teeny little aside, and it was just put in as a joke. But that was when the comic was right at its peak, in about 1989, and we were sent absolutely masses of stuff. We had a spare room in the office which became known as the porn room because it was all stacked up in there until we could throw it out. When you have 1.3 million readers, if you do put in a silly request to people to send in things, you can be quite overwhelmed by the results.

Did your experience working on Viz help when you started writing the book?

It was always little news stories, they'd never be more than 500 words, and always parodying the style of a newspaper or adverts in newspapers, or individual people's columns – you might write a column like Michael Winner and then you might do one like Gary Bushell.

After doing that for twenty years, when I went to write the book I found that I hadn't developed a writing style of my own yet. So when I started writing the book it was like going straight back to school in about 1974 and it was exactly the sort of stuff I'd written in my English essays. And it wasn't very good, to be honest, so it took me while to get the hang of writing the book.

Someone described it in Time Out as "clunky". I don't think it was meant as a compliment, but I like that word. Clunky writing style, which actually means heavy and ungainly, but it sounds fine to me.

What do you think of Viz these days?

Unfortunately, the pressure has started to tell because the frequency has gone up to ten issues a year from six, and the staff has been cut a bit. Basically it's the same from when I left, it hasn't changed that much from 1999. They're still over-reliant on some formulas which are out of date now, but it was always the case that just to get the comic filled we had to revert to formula. So there's still the same uninspired things in it, but there's still the same flashes of genius as well. It's still worth reading.

People say it's not as funny as it used to be, but it's like television. People say, "Oh, television these days isn't as good as it used to be", but they forget that for every very good programme, the Likely Lads or whatever, there was the Black and White Minstrel Show as well. People just remember the good bits and forget the bad bits. So Viz was always indifferent.

That's a bit harsh.

Well, parts of it were. You show me any issue and I'll show you at least three things I didn't like. But perhaps that's just me being fussy.

Is there any Viz character you'd like to see on screen, if it was done right?

It's quite difficult to envisage any of them being done by anybody else. Really what you'd want somebody to do would be to take it away and make it their own, but having said that I've complained that [with] the Fat Slags [movie] we didn't have any artistic input.

It would be nice to collaborate with somebody who we got on with rather than what we've always done in the past which is just hand stuff over to other people who've then gone away and made not entirely to scratch animations or videos.

I would have liked to have seen a children's cartoon of The Pathetic Sharks. That would have been quite nice. They would have had a bit of mileage in them, but unfortunately we touted that idea around and nobody was interested.

What would be your advice to people trying to get into the comics business?

I would do it for fun, primarily. A lot of comics started off in the wake of Viz that were clearly aiming to make a lot of money, to cash in on the Viz success. But we did Viz for six years before it made any money, so they should do it for fun and be prepared just to do it for fun and then hopefully as it catches on, it might start to become viable.

Also, just get work published wherever you can as well. I had cartoons in a magazine called Oink! and I had a cartoon in a magazine called Escort which I wasn't so proud of, but I used to send cartoons off to various places just to get work published, so certainly find an outlet for stuff that you can do.

Is it worth people sending submissions to Viz?

Yes. I must admit in the heady days when we were at our peak we must have had a box of stuff arriving every day, and I literally didn't have time to go through it all and there were a few boxes that got put in the bin without even being opened, it was that mad. But nowadays I know they are always looking for new stuff, and they have broken in a few new cartoonists in the past year, because the frequency of the magazine has gone up and the number of full time staff has gone down.

What's your feelings about the state of the market for humour comics?

It's always been a little bit sparse. I'm a bit out of touch these days, but I know when we first started there was Knockabout Books which was based in Kensal Road in London. They were more American Freak Brothers style things, and then there were the superhero side of the market which I've always thought was completely different to us.

We used to go to comic art conventions and meet with all these superheroey people and Alan Moore and proper comic artists, and they didn't really take us seriously. I remember one time I had to draw a cartoon for a folio of cartoons that was given away to all the guests at this comic art convention and there were pictures of the Hulk and there were pictures of Batman and all these really well drawn pictures and then a really terrible picture of Felix and his amazing underpants that I did. So we never really felt part of the British comic scene – we always felt like gatecrashers.

What are you up to next?

Well, I'm being pressurised to write another book, although it took me a year to write Rude Kids, and I did it in my own time, without a publisher.

Now my agent is saying, "We'd like another book, can you do another book by February."ú Which if you look at the calendar is only a few months away, but that's the way it goes, success breeds people ringing you up asking you to do unrealistic things. So at the minute I'm trying not to write another book. If I do I'll take another year to do it, and not be hurried into it.

Maybe you should do one about trainspottingå

I have actually suggested that, I've suggested loads of things just to wind them up. I suggested, as a joke, a Davinci Code about trainspotters searching for a mystic train number that they're all trying to collect. [The agent] thought I was serious, and asked me when I could have a synopsis ready by. They are actually quite keen on the idea of a book about trains and trainspotting. Which I may possibly do, but I would have to think about it for months or possibly years before I started.

I hope this doesn't sound rude, but from reading Rude Kids you seem to be a one of life's natural bookkeepers.

Yes, you could say that. I'm an obsessive sort of person, yes. I had a friend who was actually worse than me for that, he actually enjoyed keeping score in cricket games, and working out batting averages. In the end he studied Statistics, and became a Post Office statistician. You meet that sort of person on railway platforms when you're a trainspotter, you get that strangely obsessive sort of person, and I suppose I am one of them, I collect things.

I collect lined books and accounting books with columns in them, and have done ever since I was a kid. I couldn't think of anything to write in them, but I just liked the books. I actually started a football team in my street, and there were two reasons: one was so that I could produce a matchday programme, because I like magazines, and the other reason was so that I could have a manager's desk and a little office. So I had a manager's office in the shed in the garden where I used to ponder team selection and things.

I was quite obsessed with the idea of having an office, and I'm still obsessed by office stationery as well. I used to work for the DHSS and I would actually steal loads of office stationery. Not staplers, that was a sacking offence if you stole a stapler, but little things like treasury tags because I used to just like them and collect them.

I used to steal chalk at school too, it's all coming back to me, from the stockroom. I used to steal boxes of anti-dust chalk, and I never had any use for them other than hoarding them in a wardrobe at home. A magpie and an obsessive, I think I am.