|

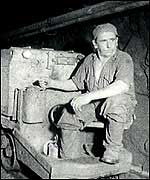

In the Blood

As a lad, John Phillips dreamed of joining the navy.

But instead ended up working long hours loading fish lorries.

When his elder brother suggested he could earn a better

living as a miner John jumped at the chance and at 25 years old began

a lifetime's toil underground.

|

| The tin mine |

John started working as a winder driver in the 1960s,

and after serving his apprenticeship he was sent down to the mine face

to drill rocks for blasting.

His job was to help expand the mine and free up the tin,

which sold - at its peak - for £8,500 a ton.

He remembers the camaraderie, but also the danger, of

life down the mine.

"You've got to know exactly what you are doing,"

he recalls.

"You've got to take great care because you've got

rock above your head as well as on the sides and a piece could fall at

any moment if you are not careful."

A Dirty Job

Quite apart from the constant danger, blasting down the

mine was a draining and physically demanding job.

|

| The mine's chemical separation tanks |

"The upper levels at Geevor would be like working

in a rainstorm," John says.

"There was cold water running on you and you were

up to your knees in mud and slush water, your boots got full up and then

you were soaking wet.

"As you got lower down it grew red hot and very

humid. You worked in just a pair of trousers and a vest and any exertion,

you started sweating.

"There were two of you in a header approximately

seven by eight foot and sometimes you never even stopped for dinner.

"We'd work, because if we didn't drill and break

the ground we'd never get any money.

"It was something you accepted because you were

a miner, and if you didn't like it you went on searching for something

on the farm. But we all loved it and once you started mining you never

finished."

The Collapse of Tin

John was a union rep at the Geevor mine when the bottom

fell out of the tin market in 1986.

He recalls how the crash came with little warning and

decimated the lives of his colleagues.

"I must have been one of the last miners to be finished

at Geevor. I was walking through the mine when it was empty.

|

| End of the line for tin |

"It was like a ghost, a ghost's mine, myself and

Jeremy Green - he was my mine captain, we had to go down and bring up

all the machines from the stopes and clean everything out and it was the

worst day's work I had to do in my mining career."

When the tin price dropped from over £8,000 a ton

to less than £3,000 a ton, the Geevor miners had put forward a proposal

to their management that they would work 9 hours a day but still only

receive 8 hours pay.

This action did enable the mine to continue operating

for a time. But the miners were fighting a losing battle.

John recalls: "Myself and my partner at the time,

Roger Pearce, we were working on 15 level doing some developing and we

had members of the DTI come in.

"I actually shook the man's hand and he said, 'I

see all the work that you are doing and I can't see a reason why the Government

won't invest the money in your mine.'

"I thought 'We are going to be reasonably safe now,

we are going to get some money from the Government', and then obviously

the money was cut off just months after that.

"It was Black Friday when I came up from underground

and I was asked by a reporter 'How do you feel about the mine shutting?'

I think it was a crying shame."

The Doomed March

The tin miners who were losing their jobs as a result

of the closures marched to London to protest - but tragic events elsewhere

overshadowed their demonstration.

|

| The Challenger shuttle explodes |

"It was going well," John says. "We were

getting a lot of support from everybody in London when we went but unfortunately

the space ship, Challenger

exploded and killed all the astronauts the same day.

"While obviously I can understand that it was far

superior news than we miners at the time, if it wasn't for that we might

have got a little something, I don't know, because I think the march was

really successful."

When the Geevor mine closed, John managed to get a job

four days a week at Leonard Cheshire Foundation at Long Lock.

He worked as a handyman, taking

people around in their wheel chairs.

"I did that for a while and then I went to work for

a haulage company, loading the lorries and whatnot for a while,"

John recalls. "Then I managed to get back to Geevor again for a short

period of time."

Jinxed

John heard through the grapevine that there was work

in Yorkshire, so he moved to Doncaster and worked in coal mines for contractor

Tysons.

"I worked for them for quite a while going round

different pits developing in the mines instead of working in the headings,"

John says. "And then I actually went and worked for the Coal Board

itself.

"Then obviously coal experienced

the same sort of problems as tin and I thought 'Aye, aye, I'm jinxed here'.

"Five or six years later the last mine I was working

at closed, and that was the end of an era. It's

something I got used to I think, being made redundant from mines."

|