"Labour's Tax Bombshell" and the Shadow Budget

It was clear going into the '92 campaign that tax was going to be a central issue. Labour had worked hard since 1987 to neutralise its image as a high tax-and-spend party. With the steady, bank manager-like John Smith as Shadow Chancellor, and the tenacious Margaret Beckett as his deputy, firm spending commitments had been kept to a minimum and Labour hoped to be able to persuade the voters that it could be trusted on tax. All Labour Party policy proposals were carefully costed and the party was determined to give the Conservatives no scope for scaring the voters with the claim that Labour would put up their taxes.

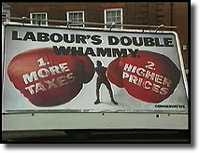

However, as early as the summer of 1991 the Conservatives had launched an offensive on Labour's spending plans, costing their proposals at £35 billion and in the New Year it became clear there would be no let up. On 6 January 1992 they unveiled the "Labour's Tax Bombshell" poster campaign, in which it was claimed Labour's plans would mean tax increases of more than £1,000 for the average voter.

In an attempt to neutralise Tory attempts to raise fears in the voters minds about hidden tax rises, Labour decided that it would produce its own Shadow Budget setting out in detail its tax and spending plans. This was presented on Tuesday 17 March, just six days into the campaign and seven days after Chancellor Norman Lamont's real Budget had been presented to the Commons.

Labour's "Budget" proposed an increase in the personal allowance of £330, of particular help to the lower paid; an increase in the top rate of tax from 40% to 50%; and removal of the exemption from 9% National Insurance contributions on high earners. Labour claimed 8 out of 10 voters would be better off under its proposals. In particular, those at the lower end of the earnings scale would be much better off.

Labour claimed that a single person on average earnings would be over £100 per annum better off and that the average two earner family with two children would be £311 per annum better off. Higher earners on the other hand would be much worse off. A married couple with one earner on £40,000 would be approximately £150 a month worse off.

During the election campaign the Shadow Budget was pretty well-received, although in hindsight many commentators claimed Labour's openness on the subject had proved a tactical error. However, it is unlikely that the Shadow Budget had any specific impact. It was an attempt by Labour to rebut Tory propaganda about its tax plans, but by the election the Conservatives long-run campaign to plant in the voters' minds the fear that they would all be worse off under Labour seemed to have borne fruit.

"Double Whammy"