|

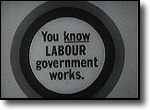

31 March 1966Labour won the 1966 election with the second largest majority in its history. Prime Minister Harold Wilson's skillful management of the country since 1964 paid Labour dividends. The Conservative leader, Edward Heath, could not compete with Wilson's popularity and failed to disturb the Prime Minister's forward march as Labour coasted to a landslide victory.

However, the Government ran into trouble in the House. It only barely survived a debate on the future of the Territorial Army and Labour backbenchers were becoming increasingly uneasy over the Government's support for American intervention in the Vietnam war. Edward Heath had replaced Sir Alec Douglas-Home as leader of the Conservative Party in 1965. And although the polls suggested he was not as popular as Wilson, he did manage to heal some of the party rifts generated by his predecessor. After Labour's crucial and unexpected by-election victory in Hull North in January 1966, a general election could never be far away. Tory hopes of winning the seat were dashed by a 4.5% swing to Labour. On 28 February, after returning from a trip to the Soviet Union, Wilson called the general election for 31 March 1966.

Labour gained 48 seats, taking them up to 363. The Conservatives lost 51 seats, leaving them with 253. The Liberals, despite seeing their share of the vote fall, gained two seats, taking them to a total of 12. The national swing to Labour was 2.7%. Wilson now had a majority of 96. He could look forward to governing for a full Parliament and working towards his ambition of making Labour the natural party of government.

|

Diana, Princess of Wales, 1961-1997

Conference 97

Devolution

The Archive

News |

Issues |

Background |

Parties |

Analysis |

TV/Radio/Web

Interactive |

Forum |

Live |

About This Site

News |

Issues |

Background |

Parties |

Analysis |

TV/Radio/Web

Interactive |

Forum |

Live |

About This Site

© BBC 1997 |

politics97@bbc.co.uk |