|

| William Wallace, became a Scottish hero after leading a Scottish army to victory over Edward I troops at Stirling Bridge |

Early Scottish History and the Union

Scotland began to emerge in some recognisable form in the ninth century. Up until then the different parts of the country were ruled over by various tribes - Picts, Britons, Scots, Angles and latterly the Norse.Between 850 and 1050 a single kingdom and a single name for what had been distinctly separate peoples began to evolve. In the early 840s Kenneth mac Alpin succeeded to the Gaelic kingdom of Dalriada and a couple of years later he became the Pictish king.

Although not the first to take this route to the Pictish throne he was the first to have descendants that maintained the link between the two kingdoms. The mac Alpins eventually become accepted as 'high kings' of Alba or Scotia, which covered a great part of modern day Scotland.

The mac Alpin line ran almost unbroken until 1034 by which time the institution of King of Scotland had been consolidated.

Medieval

The eleventh and twelfth centuries saw the development of a 'hybrid kingdom', one part of which was governed by a mixture of a feudal government and Celtic custom.

The position of King of the Scots was further consolidated in this period but the realm was coming under increasing attention from the Anglo-Norman kings of England. Between 1296-1424 Scotland and England engaged in almost continuous warfare.

By this time Scotland had forged distinct territorial boundaries and a national identity - a trend intensified by war. From this period, now referred to as the Wars of Independence, came many of the symbols of modern Scottish nationalism - William Wallace, Robert Bruce, Bannockburn and the Declaration of Arbroath.

The Declaration of Arbroath (1320) rejected the claim of the kings of England to the Scottish throne and emphasised the priority of the Scottish community over the authority of any king. The fifteenth century, after the almost constant warring, was a period of national consolidation. The wars had thrown up a coherent political community and the new line of Stuart kings provided able leadership.

Reformation

The Calvinist inspired John Knox brought the highly democratic form of Presbyterian worship to Scotland. Knox's religion was totally at odds with the seventeenth century Stuart monarchy which still held to the 'Divine Right of Kings'.

Despite its increasing harshness in this period, Presbyterianism was accepted by the majority of Scots. When Charles I tried to impose the Anglican form of worship on Scotland in the 1630s, the resistance it inspired was one of the causes of the English Civil Wars. Scotland was keen to see the establishment of its form of government in England but the Puritans were ultimately rejected and the monarchy restored.

Union

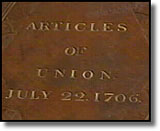

|

| The Articles of Union, which formed the basis of The Act of Union of 1707 |

The Act of Union of 1707 united the parliaments of England and Scotland. However, Scotland retained its own church, the Kirk, and a separate legal system.

Scotland at this time was at a very weak point - there had been serious famines and an attempt to establish a Scottish colony in Central America, the Darien scheme, had failed costing many Scots large amounts of money.

To sign up to the Act of Union was seen as a decision of the ruling classes. They had an interest in preserving trade with England and their decision was unpopular with the rest of the country.

In the initial period after the union the economy suffered as Scotland fought to become competitive in the larger British market. However, in the long run Scotland benefited economically from the Union.

The tobacco trade with the English colonies in North America turned Glasgow into a boom town and the stability which British troops provided in the aftermath of the 1745 Jacobite rebellion (Bonnie Prince Charlie failed in his attempt to take the British throne) allowed Edinburgh to expand beyond its unhealthy and protective huddle around the castle.

Both cities became 'hotbeds of genius' during the Scottish Enlightenment which gathered pace as the eighteenth century progressed.

After the failure of the final Jacobite rebellion, nationalism declined among the aristocracy, and Scots law moved towards increased political convergence with England.

Scotland was now removed from the fear of war, both against England and internally. The idea of Scotland as 'North Britain' was popularised among the aristocracy and intelligentsia and Scottish men went forward to fully participate in the British Empire at all levels.

Nineteenth Century

The Industrial Revolution transformed Scotland. The textile industry quickly produced a skilled and politically active working class. However, sectarian divisions, created by the immigration of large numbers of Irish Protestants and Catholics, handicapped the development of trade unionism and blurred political allegiances.

The assimilation to the English franchise gave middle class Scots a better opportunity to make their voices heard at Westminster. For the next 50 years the dominant force in Scottish politics was the Liberal Party.

The Liberals were faithfully returned at the polls even when both Ireland and Wales were developing powerful Home Rule parties. The Liberals were seen by the Scottish as a reliable enough vehicle for their home rule ambitions.

By the end of the century there was significant momentum in the home rule movement. A Scottish Home Rule Association was founded in 1886. More importantly, by 1885 the Liberal leader, William Gladstone, had become converted to the idea of home rule.

Between 1889 and 1914 Scottish home rule was debated 15 times in Parliament, including the introduction of four bills. In 1913 a Home Rule Bill passed its second reading. World War I then intervened and the idea was dropped but support for home rule had been on the wane in any case, as campaigning for it meant associating with the more outspoken Irish home rule activists. This alienated support within Scotland both for the Liberals and constitutional change.

Nevertheless, a discrete administrative system was established for Scotland. The post of Secretary for Scotland was formed in 1885 supported by a Scottish Office. It became a cabinet position in 1926. In 1895 a Scottish Grand Committee was established with powers to discuss Scottish legislation and in 1948 the Standing Committee on Scottish Bills was given powers to consider bills relating to Scotland. In 1957 it was renamed the Scottish Grand Committee.

The Devolution Debate in the 20th Century