Scotland Decided - The Referendum

11 September 1997

by Brian Taylor, Political Editor, BBC Scotland

The exasperation was tangible. In a sense, we had waited since 1707 for a verdict on whether Scotland's Parliament was to be restored - and of course the early results left no doubt as to the outcome. So a little patience might have been expected. But we had yet to witness the final, comprehensive declaration. It was well past five o'clock in the morning and one council area - Highland - had still to complete its scrutiny of the votes. We knew they had to gather votes from a local authority area the size of Belgium. We knew that other declarations had been substantially delayed while the figures were checked between the local count and the central site in Edinburgh. We knew, we sympathised. But still the irritation was palpable.

|

| The Eurovision style voting was a big hit |

There were, however, two main changes from the Eurovision format. Firstly, the event wasn't held in Dublin which appears to be compulsory for the musical version. Secondly, the remote counts were not Edinburgh's to command. Presumed variations in attitudes to devolution across the regions of Scotland had been a key element of the referendum campaign. Consequently, it was important to determine whether those variations were borne out in practice - and to what extent.

Still we waited. I was in BBC Scotland's main television studio, taking part in a results programme broadcast throughout the UK. We had reported the individual declarations, we had analysed the impact. Now we were reduced to literature.

Alex Salmond parodied T.S Eliot (Scotland, it seems, had voted "not with a whimper but with a bang"). I turned to W.B. Yeats ("...all changed, changed utterly"). Still we waited. The authors brought to mind now were Kafka and Lewis Carroll as our televised dawn discussions became ever more surreal.

Finally the Highland figures came through and this exercise in political painting-by-numbers was complete. Scotland had voted decisively Yes/Yes. True, there were variations. But the question marks which had been essayed by critics earlier didn't survive the final scrutiny.

First, turnout. At 60.4 per cent, it was enough to withstand potential gripes that the people of Scotland had not demonstrated sufficient interest for the project to go ahead wholeheartedly.

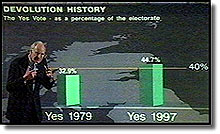

Those attempting to muster such an argument met a series of responses. No region of Scotland produced a turnout of less than 50 per cent. The maximum potential figure was deflated somewhat by the impact of an outdated electoral register. The voters' response - while down on general election levels - was higher than for council ballots. The turnout was only marginally down on the 1979 referendum when 63.04 per cent of voters in Scotland had registered their preferences.

More significantly, the result on the first question - the principle of a devolved Parliament - was beyond question. From figures like 84.7 per cent support in West Dunbartonshire through 83.6 in Glasgow and 71.9 in Edinburgh down to 61.7 in East Renfrewshire and (the lowest) 57.3 per cent in Orkney, Scotland had said Yes.

|

| 1979 v 1997 |

Next, taxation. Tony Blair was adamant that the Parliament's potential power to vary the standard rate of income tax must be tested separately. On this question, support was generally around ten per cent less than for the principle of devolution. Two areas indeed - Orkney and Dumfries & Galloway - voted against this power.

But the proposal still comfortably passed the electoral test - although perhaps the narrower majority and the apparent disquiet in parts remote from the central belt might influence future Scottish Parliamentarians to treat the taxation power with additional discretion. It would appear, then, that devolution was indeed the "settled will" of the Scottish people - the phrase regularly used by the former Labour leader John Smith. It would appear that there was a quiet, undemonstrative determination for that will to be exercised.

|

| Tommy Graham: at the centre of the Renfewshire rammy |

The No camp have for the most part been resignedly gracious in defeat - and, more narrowly, the Scottish Conservatives have indicated that their standpoint will change. Insiders recognised that root-and-branch opposition to devolution could only truly be a strategy to take the party through the referendum.

Such a strategy had the merit of consistency with the approach adopted by the party in government. In addition, the hope was that the Labour Government might suffer an embarrassing defeat on the tax question: a defeat which, it was felt, might have been enough to destabilise the wider reform programme and tarnish the Prime Minister.

There was always, however, an opt-out clause. It was made plain that, should the Scottish people vote for a devolved Parliament, then the Tories would seek to represent Right-of-centre thinking in that body. The proportional voting system devised for that Parliament should ensure them a presence.

Now it's acknowledged - indeed, to be frank, it was always acknowledged - that the Scottish party must change in keeping with the apparent mood. There must be an avowedly Scottish dimension to Tory policy-making and presentation in Scotland. Whoever leads the Tory group in the putative Scottish Parliament will be the leader of the party in Scotland. It's yet another change to accommodate for the party whose ancestors bitterly opposed the Union with England, which achieved the only post-war popular majority by a party in Scotland (50.1 per cent in 1955) and which currently has no MPs at Westminster from Scottish constituencies.

Labour too will face change. There will be pressure for the devolution of policy-making to Scotland to be accelerated. MPs presently at Westminster will have to decide where their future lies. Might they find time dragging a little in London once Scottish business has been transferred to Edinburgh? Might they even find their presence faintly resented? Or do they believe the attractions of the wider Westminster stage over-ride such considerations? If they do opt for Edinburgh, would they pass the scrutiny of Labour's tight new candidate vetting system?

The Liberal Democrats and the SNP will obviously seek to maintain the status which their consensual support for the Yes camp supplied. Already, they have speculated about a role in helping draft the detailed working arrangements for the Parliament. In the longer term, they might face the choice of entering a coalition government with the Labour Party in that Edinburgh Parliament.

Against that, I feel it would be an error to make too much of this consensus factor. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the SNP combined for very good individual reasons in the Yes camp. Broadly speaking, the LibDems - with a century behind them of campaigning for Home Rule - had part-authorship of the scheme as members of the constitutional Convention alongside Labour in opposition. The Nationalists concluded that the reform on offer - while well short of their objective of independence - represented an advance which they shouldn't reject.

|

| Wallace and Salmond in the van |

Yet there remain fundamental political differences: particularly between Labour and the SNP. Those differences consequently will - and should - be reflected in political debate. It's a question of choice for the electorate.

So what now? A detailed Bill, for starters, which will be published later this year and will have to progress through both Houses of Parliament. The aim is to hold elections to the Scottish Parliament in the first half of 1999 - with full devolution of power from the start of the year 2000.

Beyond that, the questions. Who'll take power? Will the voting system - a combination of first-past-the-post constituencies and regional party lists - work efficiently? Who'll be Scotland's first First Minister? Will there be pressure to use the tax power? Will there be pressure from Whitehall to cut the block grant available to Scotland? Above all, will it bind or break the Union?

The answers - particularly to the last question - depend of course upon subsequent developments. Those who support the Union say it is best bulwarked by a rolling programme of reform to make Britain's constitutional structure responsive to modern needs. Nationalists contend that the Scots - who have consistently declined to vote for independence - may become more contented with the prospect once devolved power is in place. A third argument is that the question itself may need to be rephrased if, across Europe, the relationship between central and "regional" tiers of government is seen to change: that the issue of autonomy may no longer be viewed in absolute terms, that Scotland may build domestic political control mechanisms while other elements - including defence and diplomacy - are apportioned between Westminster and Europe. For now, though, Scotland has most definitely voted for the devolution settlement on offer from the Government.

While that in itself carries portents of radical change, this was a quiet revolution. It's entirely possible that the campaign had minimal impact upon the result: that the people had quite simply made up their minds. In such circumstances, it's perhaps understandable that the atmosphere peaked a little below the frantic.

Not that the Labour machine didn't try its best in Edinburgh the day after the referendum. The venue chosen was Parliament Square - where Scotland's previous democratic assembly was adjourned nearly three centuries ago. Sheboom - a band of enthusiastic and talented female drummers - provided a confident beat. Yes/Yes banners mingled with the emblem of Scotland, the Saltire. Tony Blair was brought by helicopter to the park next to Holyrood Palace - then up the Royal Mile.

The blend of history and contemporary politics could scarcely have been more intense. And yet it was all contained. The atmosphere - even among the assembled crowd - was of contentment, a task completed.

|

| 'most satisfactory' |