The stick touched, and nothing happened.

I did it again. Same result. We stopped walking. My legs ached and I was glad for the break.

Pete hesitated a beat, then reached out and brushed the thick black wire with his hand. When we were kids he might have pretended it was charged, and jiggered back and forth, eyes rolling and tongue sticking out.

He didn't now. He just curled his fingers around it, gave it a light tug.

"Power's down," he said, quietly.

Henry and I stepped up close. Even with Pete standing there grasping it, you still had to gird yourself to do the same.

Then all three of us were holding the fence, holding it with both hands, looking in.

That close up, the wire fuzzed out of focus and it was almost as if it wasn't there. You just saw the forest beyond it: moonlit trunks, snow; you heard the quietness. If you stood on the other side and looked out, the view would be exactly the same. With a fence that long, it could be difficult to tell which side was in, which was out.

This, too, was what had happened the previous time, when we were fifteen. We'd heard that sometimes a section went down, and so we went looking. With animals, snow, the random impacts of falling branches and a wind that could blow hard and cold at most times of year, once in a while a cable stopped supplying the juice to one ten yard stretch. The power was never down on for more than a day. There was a computer that kept track, and - somewhere, nobody knew where - a small station from which a couple of military engineers could come to repair the outage. It had happened back then. It had happened now.

We stood, this silent row of older men, and remembered what had happened then.

Pete had gone up first. He shuffled along to one of the concrete posts, so the wire wouldn't bag out, and started pulling himself up. As soon as his feet left the ground I didn't want to be left behind, so I went to the other post and went up just as quickly.

We reached the top at around the same time. Soon as we started down the other side - lowering ourselves at first, then just dropping, Henry started his own climb.

We all landed silently in the snow, with bent knees.

We were the other side, and we stood very still. Far as we knew, no-one had ever done this before.

To some people, this might have been enough.

Not to three boys.

Moving very quietly, hearts beating hard - just from the exertion, none of us were scared, not exactly, not enough to admit it anyway - we moved away from the fence.

After about twenty yards I stopped and looked back.

"You chickening out?"

"No, Henry," I said. His voice had been quiet and shaky. I took pains that mine sound firm. "Memorising. We want to be able to find that dead section again."

He'd nodded. "Good thinking, smart boy."

Pete looked back with us. Stand of three trees close together there. Unusually big tree over on the right. Kind of a semi-clearing, on a crest. Shouldn't be hard to find.

We glanced at each other, judged it logged, then turned and headed away, into a place no-one had been for nearly ten years.

The forest floor led away gently. There was just enough moonlight to show the ground panning down towards a kind of high valley lined with thick trees.

As we walked, bent over a little with unconscious caution, part of me was already relishing how we'd remember this in the future, leaping over the event into retrospection. Not that we'd talk about it, outside the three of us. It was the kind of thing which might attract attention to the town, including maybe attention from this side of the fence.

There was one person I thought I might mention it to, though. Her name was Lauren and she was very cute, the kind of beautiful that doesn't have to open its mouth to call your name from across the street. I had talked to her a couple times, finding bravery I didn't know I possessed. It was she who had talked about Seattle, said she'd like to go hang out there some day. That sounded good to me, good and exciting and strange. What I didn't know, that night in the forest, was that she would do this, and I would not, and that she would leave without us ever having kissed.

I just assumed... I assumed a lot back then.

After a couple of hundred yards we stopped, huddled together, shared one of my cigarettes. Our hearts were beating heavily, even though we'd been coming downhill. The forest is hard work whatever direction it slopes. But it wasn't just that. It felt a little colder here. There was also something about the light. It seemed to hold more shadows. You found your eyes flicking from side to side, checking things out, wanting to be reassured, but not being sure that you had been after all.

I bent down to put the cigarette out in the snow. It was extinguished in a hiss that seemed very loud.

We continued in the direction we'd been heading. We walked maybe another five, six hundred yards.

It was Henry who stopped.

Keyed up as we were, Pete and I stopped immediately too. Henry was leaning forward a little, squinting ahead.

"What?"

He pointed. Down at the bottom of the rocky valley was a shape. A big shape.

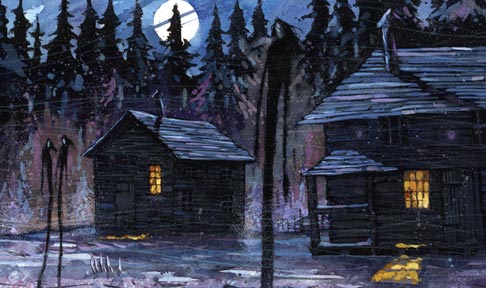

After a moment I could make out it was a building. Two wooden storeys high, and slanting.

You saw that kind of thing, sometimes. The sagging remnant of some pioneer's attempt to claim an area of this wilderness and pretend it could be a home.

Pete nudged me and pointed in a slightly different direction. There was the remnants of another house further down. A little fancier, with a fallen-down porch.

And thirty yards further, another: smaller, with a false front.

"Cool," Henry said, and briefly I admired him.

We sidled now, a lot more slowly and heading along the rise instead of down it. Ruined houses look real interesting during the day. At night they feel different, especially when lost high up in the forest. Trees grow too close to them, pressing in. The lack of a road, long overgrown, can make the houses look like they were never built but instead made their own way to this forgotten place, in which you have now disturbed them; they sit at angles which do not seem quite right.

I was beginning to wonder if maybe we'd done enough, come far enough, and I doubt I was the only one.

Then we saw the light.

|

|